Multi-Env Nautobot deployment to ECS Fargate with CDK (Typescript)

Recently at work, I’ve been challenged with understanding numerous packages that deploy Infrastructure as Code (IaC) in Typescript using the Cloud Development Kit (CDK). Recognizing this, I decided it was time to delve into CDK and concurrently learn Typescript. Being an a fan of Terraform, I presumed the transition would not be too daunting, and indeed, it wasn’t. In this post, I will outline how I deployed Nautobot to Amazon Web Services (AWS) Elastic Container Service (ECS) Fargate using CDK.

The deployment process creates a development and production instances, leveraging native AWS resources such as Relational Database Service (RDS), Elastic Container Registry (ECR), ECS, Fargate, Secrets Manager, and several Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) components. The application sits behind an Application Load Balancer (ALB), with a target towards an NGINX container that acts as a reverse proxy.

Additionally, I thought it would be interesting to deploy necessary IAM Roles and Service Policies to use AWS Session Manager for ECS Fargate. This allows you to connect to the containers within an ECS Cluster without the need to manage Secure Shell (SSH) keys or bastion hosts. Although I won’t go into too much detail about how to use AWS Session Manager in this post, you can learn more by checking out the AWS Docs.

I found the simplification of Docker Images through CDK quite impressive. While it’s common to have a pipeline set up to build new images in a different repository, for this project I utilized the DockerImageAsset construct and directly built and pushed images to ECR using CDK.

For this post, I’m assuming you have a basic understanding of CDK. If not, I highly recommend checking out the CDK Workshop. Also, Nautobot is an open-source network automation platform built on Django and Python. Again, I won’t delve into the specifics of Nautobot, but for those interested, the Nautobot Docs can provide further insight.

I don’t intend to overwhelm you with an abundance of details, but will provide high-level information on aspects I found most intriguing, and explain certain approaches in the code. For more content, refer to the README.md in the repository itself. This post will serve as an entry point into the repository code.

TLDR

Deploy a multi-environment (dev/prod) Nautobot instance to AWS ECS Fargate with CDK. Github Code

- Clone the CDK-Nautobot repository.

- Edit the

lib/secrets/env-exampleandlib/nautobot-app/.env-examplefiles and rename them to .env. - Customize the

lib/nautobot-app/nautobot_config.pyfile as per your requirements. - Bootstrap the CDK application using

cdk bootstrap. - Execute the

deploy.shscript with the--stageoption to deploy to eitherdevorprodenvironment. - Approximately 20 minutes later, you will have a dev and prod Nautobot instance running in AWS.

Stacks

The unit of deployment in the AWS CDK is called a stack.

All AWS resources defined within the scope of a stack, either directly or indirectly,

are provisioned as a single unit.

I decided to break down my stacks as followed:

Database Stacks- This stack will create a Redis and Postgres RDS instance.Nautobot Docker Image Stack- This stack will create a Docker image of Nautobot and push it to ECR.Farage ECS Stack- This stack will create the ECS Cluster, Task Definition, and Service including SSM necessary items.Secrets Manager Stack- This stack will create the secrets needed for Nautobot container. This includes the database credentials, superuser credentials, and the secret key, etc.VPC Stack- This stack will create the VPC, subnets, and security groups needed for the Nautobot instance, plus the Load Balancer.Nginx Docker Image Stack- This stack will create a Docker image of Nginx and push it to ECR. This is used as a reverse proxy to the uWSGI server on the Nautobot container.

Directory Tree

➜ lib git:(develop) ✗ tree

.

├── cdk.out

│ └── synth.lock

├── nautobot-app

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ ├── nautobot_config.py

│ ├── README.md

│ └── requirements.txt

├── nautobot-db-stack.ts

├── nautobot-docker-image-stack.ts

├── nautobot-fargate-ecs-stack.ts

├── nautobot-secrets-stack.ts

├── nautobot-vpc-stack.ts

├── nginx

│ ├── Dockerfile

│ └── nginx.conf

├── nginx-docker-image-stack.ts

└── secrets

└── env-example

4 directories, 14 files

Bootstrapping Multi-Environments

A great feature of CDK is the bootstrapping process will create a CloudFormation stack that contains resources needed for deployment. This includes an S3 bucket to store templates and assets, and an IAM role that grants the AWS CDK permission to make calls to AWS CloudFormation, Amazon S3, and Amazon EC2 on your behalf. I kind of thought about this as configuring a S3 Backend for Terraform.

The snippet below is from bin/cdk-nautobot.ts file. This calls the app.synth() function which will synthesize the CDK app into a CloudFormation template and deploy it to the AWS account and region specified in the constants file. As you can see below, there is a simple for loop that will iterate over each environment and deploy the stacks. The application will detect multiple accounts in the form of Environments. In my case, I’m only using 1 AWS account, but you can easily add more accounts and regions to the Environments object.

It’s important to note, that in my case I did not share any resources from one environment with another.

// Environments configuration

// This makes it simple to deploy to multiple environments such as dev, qa, prod

const getEnvironments = async (): Promise<Environments> => {

const accountId = await getAccountId();

return {

dev: { account: accountId, region: 'us-west-2' },

prod: { account: accountId, region: 'us-east-1' },

};

};

(async () => {

const app = new cdk.App();

// <.. omitted ..>

// Iterate over each environment

for (const [stage, env] of Object.entries(stages)) {

const stackId = `${stage}NautobotVpcStack`;

const stackProps = { env: env };

const nautobotVpcStack = new NautobotVpcStack(app, stackId, stage, stackProps);

// <.. omitted ..>

}

app.synth();

})();

Docker Builds and Secrets

I’m not entirely certain about the best practices for using CDK, but I found my approach effective and helpful. I utilized the dotenv library to parse the .env file and create Secrets in AWS Secrets Manager. Subsequently, I used the DockerImageAsset resource to build and push Docker images to the Elastic Container Registry (ECR). Since each retrieval from the API incurs a cost, it’s crucial to ensure that only sensitive information is stored in the Secrets Manager.

CDK provides the DockerImageAsset class to make it easy to build and push Docker images to Amazon ECR. The DockerImageAsset class is a subclass of the Asset class, which is used to represent local files and directories that are needed for a CDK app. The Asset class is used to upload the local files to an S3 bucket, and then the DockerImageAsset class is used to build and push the Docker image to Amazon ECR.

Example of the DockerImageAsset resource:

import { DockerImageAsset, NetworkMode } from '@aws-cdk/aws-ecr-assets';

const asset = new DockerImageAsset(this, 'MyBuildImage', {

directory: path.join(__dirname, 'my-image'),

networkMode: NetworkMode.HOST,

})

The pattern I developed to load secrets, which are essential for the proper functioning of the Nautobot application, involves using a common .env file and pushing these variables solely to the Secrets Manager. Here’s a snippet from the Secrets Stack:

// Path to .env file

const objectKey = ".env";

const envFilePath = path.join(__dirname, "..", "lib/secrets/", objectKey);

// Ensure .env file exists

if (fs.existsSync(envFilePath)) {

// Load and parse .env file

const envConfig = dotenv.parse(fs.readFileSync(envFilePath));

// Iterate over each environment variable

for (const key in envConfig) {

// Get the value

const value = envConfig[key];

// Check that the value exists and isn't undefined

if (value && value !== "undefined") {

// Create a new secret in Secrets Manager for this environment variable

const secret = new secretsmanager.Secret(this, key, {

secretName: key,

generateSecretString: {

secretStringTemplate: JSON.stringify({ value: value }),

generateStringKey: "password",

},

});

// Add the secret to the secrets object

this.secrets[key] = ecs.Secret.fromSecretsManager(secret, "value");

}

These secrets were passed into the Nautobot container definition via the NautobotFargateEcsStack as shown below. The Class constructor includes the secretsStack as a parameter. This allows the NautobotFargateEcsStack to access the secrets created in the SecretsStack.

...

export class NautobotFargateEcsStack extends Stack {

constructor(

scope: Construct,

id: string,

stage: string,

dockerStack: NautobotDockerImageStack,

nginxStack: NginxDockerImageStack,

secretsStack: NautobotSecretsStack,

...

...

const nautobotWorkerContainer = nautobotWorkerTaskDefinition.addContainer("nautobot-worker", {

image: ContainerImage.fromDockerImageAsset(dockerStack.image),

logging: LogDrivers.awsLogs({ streamPrefix: "NautobotWorker" }),

environment: environment,

secrets: secretsStack.secrets,

...

The actual sharing of attributes is done in the main application file bin/cdk-nautobot.ts. Here is a small snippet showing how const variables get created and for each stack, the const variables are passed into the constructor where applicable.

for (const [stage, env] of Object.entries(stages)) {

const stackIdPrefix = `${stage}`;

const vpcStackProps = { env: env };

const nautobotVpcStack = new NautobotVpcStack(

app, `${stackIdPrefix}NautobotVpcStack`, stage, vpcStackProps);

const dbStackProps = { env: env };

const nautobotDbStack = new NautobotDbStack(

app, `${stackIdPrefix}NautobotDbStack`, nautobotVpcStack, dbStackProps);

...

);

}

Redis and Postgress RDS

Although this stack seems to take the longest to deploy, it is by far the simplest configuration in the stacks. I found the CDK constructs for RDS really simplified the process of deploying postgress. The Username, Password and DB Name are all a simply attribute to the DatabaseInstance.

// Create an Amazon RDS PostgreSQL database instance

this.postgresInstance = new rds.DatabaseInstance(this, 'NautobotPostgres', {

engine: rds.DatabaseInstanceEngine.postgres({

version: rds.PostgresEngineVersion.VER_13_7,

}),

instanceType: instanceType,

credentials: rds.Credentials.fromSecret(this.nautobotDbPassword),

vpc: vpc,

vpcSubnets: {

subnetType: ec2.SubnetType.PRIVATE_WITH_EGRESS,

},

multiAz: true,

allocatedStorage: 25,

storageType: rds.StorageType.GP2,

deletionProtection: false,

databaseName: 'nautobot',

backupRetention: Duration.days(7),

deleteAutomatedBackups: true,

removalPolicy: RemovalPolicy.DESTROY,

securityGroups: [dbSecurityGroup],

});

From the DB Stack, we create the postgresInstance and redisCluster objects. Additionally, we create the nautobotDbPassword as a Secret object.

export class NautobotDbStack extends Stack {

public readonly postgresInstance: rds.DatabaseInstance;

public readonly redisCluster: elasticache.CfnCacheCluster;

public readonly nautobotDbPassword: Secret;

Below, the NautobotFargateEcsStack accepts these values as parameters in the constructor. This allows the NautobotFargateEcsStack to access the postgresInstance and redisCluster objects. The great thing about typescript is.. type hints. You define the parameter and the type of the parameter. This makes it easy to know what you’re passing into the constructor.

export class NautobotFargateEcsStack extends Stack {

constructor(

scope: Construct,

id: string,

stage: string,

dockerStack: NautobotDockerImageStack,

nginxStack: NginxDockerImageStack,

secretsStack: NautobotSecretsStack,

vpcStack: NautobotVpcStack,

dbStack: NautobotDbStack,

...

let environment: { [key: string]: string } = {

// Make sure to pass the database and Redis information to the Nautobot app.

NAUTOBOT_DB_HOST: dbStack.postgresInstance.dbInstanceEndpointAddress,

NAUTOBOT_REDIS_HOST: dbStack.redisCluster.attrRedisEndpointAddress,

...

However, because the nautobotDbPassword was a Secret object for AWS Secrets Manager, the approach was slightly different. Container Definitions let you pass in secrets directly.

A great article on Passing sensitive data to a container

// update secrets w/ DB PW

secretsStack.secrets["NAUTOBOT_DB_PASSWORD"] = ecs.Secret.fromSecretsManager(

dbStack.nautobotDbPassword,

"password"

);

const nautobotWorkerContainer = nautobotWorkerTaskDefinition.addContainer("nautobot", {

image: ContainerImage.fromDockerImageAsset(dockerStack.image),

logging: LogDrivers.awsLogs({ streamPrefix: "NautobotApp" }),

environment: environment,

secrets: secrets,

...

This kept this as simple as possible to deploy the DB in a separate stack and use these values for our application.

Fargate Service - Nginx Reverse Proxy behind ALB

In our setup, the Nautobot container runs a uWSGI server, following the model of the official Docker image entry point. All incoming requests are handled by the Application Load Balancer (ALB) that routes them to the NGINX container. The NGINX container then forwards these requests to the uWSGI server on port 8080 of the Nautobot container. In essence, the ALB directs traffic towards the NGINX container which acts as a proxy to the uWSGI server on the Nautobot container. This is why the ALB Listener and Targets point to port 80 on the NGINX container.

Nautobot container entry point

# Run Nautobot

CMD ["nautobot-server", "start", "--ini", "/opt/nautobot/uwsgi.ini"]

ALB configuration which has a HTTP listener on port 80 and forwards to point 80.

const listener = alb.addListener(`${stage}Listener`, {

port: 80,

protocol: ApplicationProtocol.HTTP,

// certificates: [] // Provide your SSL Certificates here if above is HTTP(S)

});

listener.addTargets(`${stage}NautobotAppService`, {

port: 80,

targets: [

nautobotAppService.loadBalancerTarget({

containerName: "nginx",

containerPort: 80

})

],

healthCheck: {

path: "/health/",

port: "80",

interval: Duration.seconds(60),

healthyHttpCodes: "200",

},

});

In our setup, the NGINX container operates as a side-car to the primary Nautobot app container within the same Fargate Service’s Task Definition. This required me to define the NGINX container within the loadBalancerTarget. I faced an issue where it was erroneously selecting the Nautobot container on port 8080 as the target, instead of the intended NGINX container. After venturing into the complexities of configuring Cluster Namespaces and CloudMap,, I realized it was unnecessary. All that was required was to specify the container name and port in the loadBalancerTarget and ensure the Nautobot container was serving uWSGI on port 8080.

// Nautobot App Task Definition and Service

const nautobotAppTaskDefinition = new FargateTaskDefinition(

this,

`${stage}NautobotAppTaskDefinition`,

{

memoryLimitMiB: 4096,

cpu: 2048,

taskRole: ecsTaskRole,

executionRole: ecsExecutionRole,

}

);

const nautobotAppContainer = nautobotAppTaskDefinition.addContainer("nautobot", {

image: ContainerImage.fromDockerImageAsset(dockerStack.image),

// If you want to use the official image, uncomment the line below and comment the line above.

// image: ecs.ContainerImage.fromRegistry('networktocode/nautobot:1.5-py3.9'),

logging: LogDrivers.awsLogs({ streamPrefix: `${stage}NautobotApp` }),

environment: environment, // Pass the environment variables to the container

secrets: secretsStack.secrets,

healthCheck: {

command: ["CMD-SHELL", "curl -f http://localhost/health || exit 1"],

interval: Duration.seconds(30),

timeout: Duration.seconds(10),

startPeriod: Duration.seconds(60),

retries: 5,

},

});

nautobotAppContainer.addPortMappings({

name: "nautobot",

containerPort: 8080,

hostPort: 8080,

protocol: Protocol.TCP,

appProtocol: ecs.AppProtocol.http,

});

const nginxContainer = nautobotAppTaskDefinition.addContainer("nginx", {

image: ContainerImage.fromDockerImageAsset(nginxStack.image),

logging: LogDrivers.awsLogs({ streamPrefix: `${stage}Nginx` }),

healthCheck: {

command: ["CMD-SHELL", "nginx -t || exit 1"],

interval: Duration.seconds(30),

timeout: Duration.seconds(5),

startPeriod: Duration.seconds(0),

retries: 3,

},

});

The above Tasks Definition / Containers get added to the Fargate Service as shown below.

const nautobotAppService = new FargateService(this, `${stage}NautobotAppService`, {

circuitBreaker: { rollback: true },

cluster,

serviceName: `${stage}NautobotAppService`,

enableExecuteCommand: true,

taskDefinition: nautobotAppTaskDefinition,

assignPublicIp: false,

desiredCount: 1,

vpcSubnets: {

subnetType: SubnetType.PRIVATE_WITH_EGRESS,

},

securityGroups: [nautobotSecurityGroup],

cloudMapOptions: {

name: "nautobot-app",

cloudMapNamespace: cluster.defaultCloudMapNamespace,

dnsRecordType: DnsRecordType.A,

},

serviceConnectConfiguration: {

services: [

{

portMappingName: "nginx",

dnsName: "nginx",

port: 80,

},

{

portMappingName: "nautobot",

dnsName: "nautobot",

port: 8080,

},

],

logDriver: ecs.LogDrivers.awsLogs({

streamPrefix: 'sc-traffic',

}),

},

});

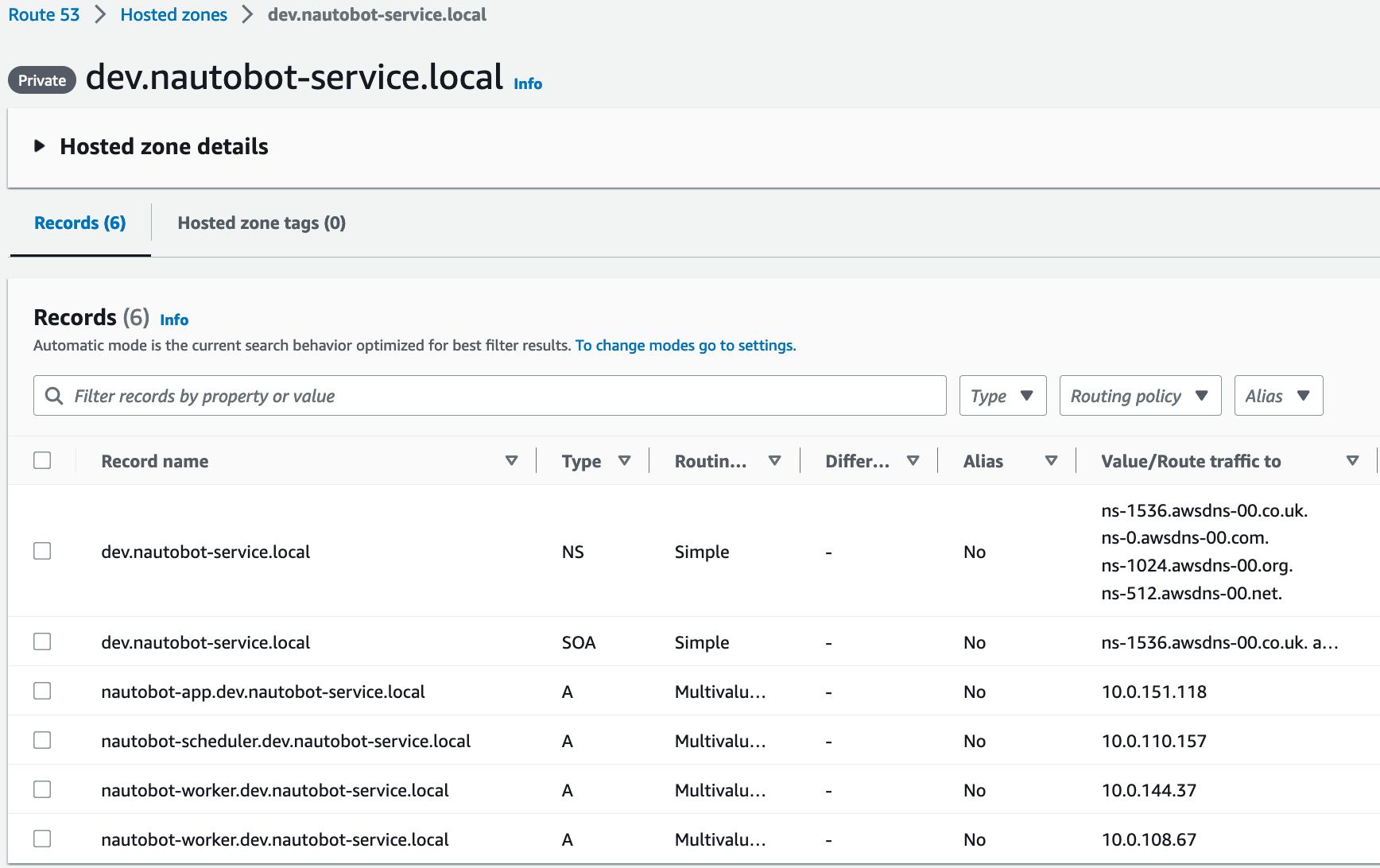

I actually did keep the Cluster Namespaces and CloudMap configuration in the code, but it’s not necessary. I left it in there for reference. I found it interesting that I could make DNS Type A records in Route53.

cloudMapOptions: {

name: "nautobot-app",

cloudMapNamespace: cluster.defaultCloudMapNamespace,

dnsRecordType: DnsRecordType.A,

},

serviceConnectConfiguration: {

services: [

{

portMappingName: "nginx",

dnsName: "nginx",

port: 80,

},

{

portMappingName: "nautobot",

dnsName: "nautobot",

port: 8080,

},

],

Route 53 DNS Type A records:

AWS Session Manager

Accessing the containers inside the cluster wasn’t a requirement, but as a developer and end-user of applications, I understand how important it can be to simply jump into a host to either debug or try something out. I’ve been using AWS Session Manager for a while now and I really enjoy it. It’s a great way to access hosts without having to manage SSH keys or bastion hosts. I figured it would be cool to add this to the Nautobot deployment.

From your machine, make sure to do this the easy way -> Pip install the AWS System Manager Tools which includes the ecs-session utility that wraps aws ecs execute-command

Install

sudo pip3 install aws-ssm-tools

So what does it take to be able to execute commands on the container or essentially, SSH into them? Well, not a lot.

- You need to have the

AmazonSSMManagedInstanceCoremanaged policy attached to the ECS Task Role. - You need to have the

AmazonSSMManagedInstanceCoremanaged policy attached to the ECS Execution Role.

// Attach the necessary managed policies

ecsTaskRole.addManagedPolicy(

ManagedPolicy.fromAwsManagedPolicyName("AmazonSSMManagedInstanceCore")

);

// Define a new IAM role for your Fargate Service Execution

const ecsExecutionRole = new Role(

this,

`${stage}ECSExecutionRole`,

{

assumedBy: new ServicePrincipal("ecs-tasks.amazonaws.com"),

roleName: `${stage}ECSExecutionRole`,

}

);

// Attach the necessary managed policies to your role

ecsExecutionRole.addManagedPolicy(

ManagedPolicy.fromAwsManagedPolicyName("AmazonSSMManagedInstanceCore")

);

// Nautobot Worker

const nautobotWorkerTaskDefinition = new FargateTaskDefinition(

this,

`${stage}NautobotWorkerTaskDefinition`,

{

memoryLimitMiB: 4096,

cpu: 2048,

taskRole: ecsTaskRole,

executionRole: ecsExecutionRole,

}

);

Additionally, the FargateService must have the enableExecuteCommand property set to true.

const workerService = new FargateService(this, `${stage}NautobotWorkerService`, {

cluster,

serviceName: "NautobotWorkerService",

enableExecuteCommand: true,

Finally, output port access to the SSM Service is required over port 443. This means the SecurityGroup for the service must allow this. The containers within fargate have the binaries mounted automatically for the ssm-agent to work. Unlike an EC2 instance, which requires a user to use Hybrid SSM to manage instances, Fargate is a managed service and the binaries are already installed, much like deploying an Amazon Linux AMI.

From Amazon blog post (Source in resources):

ECS Exec leverages AWS Systems Manager (SSM), and specifically SSM Session Manager, to create a secure channel between the device you use to initiate the “exec“ command and the target container. The engineering team has shared some details about how this works in this design proposal on GitHub. The long story short is that we bind-mount the necessary SSM agent binaries into the container(s). In addition, the ECS agent (or Fargate agent) is responsible for starting the SSM core agent inside the container(s) alongside your application code. It’s important to understand that this behavior is fully managed by AWS and completely transparent to the user. That is, the user does not even need to know about this plumbing that involves SSM binaries being bind-mounted and started in the container. The user only needs to care about its application process as defined in the Dockerfile.

Accessing Container

List the available sessions based on default profile available (aws CLI)

➜ cdk-nautobot git:(develop) ✗ ecs-session --list

devNautobotCluster service:devNautobotAppService f8ade6908843479caf9cc026bb2d81bd ecs-service-connect-cAelZ 10.0.151.118

devNautobotCluster service:devNautobotAppService f8ade6908843479caf9cc026bb2d81bd nautobot 10.0.151.118

devNautobotCluster service:NautobotSchedulerService 7d9748eaaf2e4b55a48cd92dabae477d nautobot-scheduler 10.0.110.157

devNautobotCluster service:NautobotWorkerService 078787791fd4464c962f147ec6d46d9a nautobot-worker 10.0.144.37

devNautobotCluster service:NautobotWorkerService ce0c8b8b594e4045afd3b00e5cfb063b nautobot-worker 10.0.108.67

devNautobotCluster service:devNautobotAppService f8ade6908843479caf9cc026bb2d81bd nginx 10.0.151.118

Start a session with the container

➜ cdk-nautobot git:(develop) ✗ ecs-session nautobot

devNautobotCluster service:devNautobotAppService f8ade6908843479caf9cc026bb2d81bd nautobot 10.0.151.118

The Session Manager plugin was installed successfully. Use the AWS CLI to start a session.

Starting session with SessionId: ecs-execute-command-07558d1d70dbbbe9f

Note: SSM defaults to logging into instances as root user. Change user to perform standard operations as expected.

# su nautobot

nautobot@ip-10-0-151-118:~$ ls

__pycache__ git jobs media nautobot.crt nautobot.key nautobot_config.py requirements.txt static uwsgi.ini

nautobot@ip-10-0-151-118:~$

Summary

This was a fun little project for me to work on here and there as I learn TypeScript and CDK. The CDK documentation is a great resource to find the correct attributes which I found myself looking up constantly. Overall, I really appreciate how easy it is to have a multi-environment application without thinking too hard about the layout of the project. Additionally, unit testing the code can be very simple, in the sense of generating the Template and evaluating the output CloudFormation template you expect. I do not have any examples in this project, but the patterns I found were very simple and easy to understand.